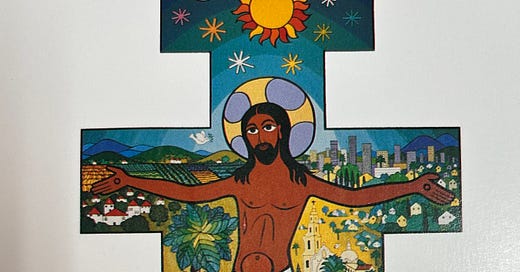

“Christ of the Americas,” painted by Fr. Arthur Poulin, a Catholic monk:

“Stay at the center, with God.”

I was listening recently to an interview with the musician Nick Cave on Krista Tippett’s On Being podcast. To be honest, I had no idea who Nick Cave was, and I wasn’t at all familiar with his music, but the interview popped up as things do and caught my eye. He talked about the death of his two sons, and about loss, yearning, transcendence and going to church. He said he prefers the word religion to the word spirituality: “Religion is spirituality with rigor,” he said. “It asks something of us.”

What does it ask? I wonder. I think of the Catholic monk David Steindl-Rast writing about faith and saying that, “Going forward in faith is not a train ride [where we just need to board the train, and then it will bring us to our destination]; it’s more like walking on water.” Walking on water suggests a way of being that is profoundly optimistic and trusting in something way beyond where reason or logic can reach.

Consider how it is when you want to jump from one stone to the next in order to cross a rushing stream. You have to go beyond thinking and completely let go of trying to control the situation. You have to leap with a kind of trust or faith that life itself will carry you from stone to stone. There is no separation, no gap between you and the stones, no second-guessing, no hesitation, no fear, no holding back, no grasping, no trying to control—in fact, there is no imagined “you” anymore, there is simply undivided movement, one whole happening, and you are that—there is only that. And you land perfectly on every stone (unless a fearful thought trips you up).

That kind of buoyancy doesn’t mean trusting that everything will turn out the way we want or that we might not be tortured or murdered. Walking on water can show up as Jesus being betrayed, falsely accused, tortured to death by crucifixion, feeling abandoned by God, and in the midst of all that, surrendering to “Thy will be done,” forgiving those who are crucifying him, and finding the (metaphorical) resurrection. It can show up as Martin Luther King Jr. on the day before he was assassinated saying to the crowd, “I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But… I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” This is walking on water. This is faith.

Faith is not the same as belief. Faith is what Jay Matthews described as staying at the center with God. In my lexicon, God is simply another word for wholeness, awareness, presence, unconditional love, no-thing-ness, openness, totality, the heart of being. What Jay is saying points to an abidance in and as wholeness. Being unconditional love. Seeing as God sees.

In my experience, this means waking up here and now, returning again and again to the openness and the listening presence that is most intimate, the boundless awareness that is always accepting everything and clinging to nothing.

And although this wholeness is never really absent, paradoxically, the realization and embodiment of it generally takes faith and perseverance, falling down and getting up again and again, feeling lost and confused and then once again returning Home. It’s not about believing an ideology. It’s trusting in something that’s not a graspable thing of any kind, something that is not “out there” at a distance. It’s THIS here-now presence that we are and that everything is. It’s closer than close, most intimate, and at the same time, all-inclusive and boundless.

God and faith are religious words, and that’s probably part of why they both resonate here. I’ve always been a religious person. I wasn’t raised in any religion, but religion has always attracted me. I’ve never really fit into any organized religion, although throughout my life, I’ve wandered in and out of various churches and Zen centers, sometimes joining them but eventually always leaving. My path seems to be solitary, nontraditional and eclectic, but my life definitely seems to center on religion—a word I’ve tended to replace with spirituality, as many others have done, but maybe religion is not such a bad word.

The whole religious engagement with life is playful but also serious, effortless yet requiring a certain kind of perseverence. In a way, it’s very much like walking on water. Walking on water sounds delightfully playful and free. The doubt that sinks us is serious, self-concerned, worried, rooted in identifying as a limited form and ignoring the whole that transcends all apparent limits.

But sinking into doubt from time to time may be an important element in the Cosmic Play. And, of course, some forms of doubt are healthy and important in waking up from false beliefs and certainties.

My favorite part of the beautiful movie Conclave was the scene where the dean, who is struggling with doubt, gives a sermon to the conclave in which he says:

“The sin I have come to fear more than any other is certainty. Certainty is the great enemy of unity… the deadly enemy of tolerance. Even Christ was not certain at the end… Our faith is a living thing precisely because it walks hand in hand with doubt. If there was only certainty, if there was no doubt, there would be no mystery, and therefore no need for faith.”

Nick Cave talks in the interview about how religion and religious ritual touches a mysterious dimension beyond logic and the rational mind.

Around the same time that I heard that interview, a friend sent me a beautiful novel, Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood. The narrator is a middle-aged woman who unplugs from her life of environmental activism and moves to a remote monastery run by a small handful of aging nuns in the middle of a barren landscape in Australia near where she grew up. The woman is an atheist. When she first attends one of their religious services, she is struck by the beauty of it, until she reads the words they are chanting, which are all about evil and sin, and then she’s quite turned off. But she keeps watching and listening, and she writes, “Watching the women, I’m convinced that the words they’re singing are meaningless; that instead, this ritual is all about the body and the unconscious mind… I kept thinking of yoga: it has the same rhythmic quiet, the same slow, feminine submission.”

That fits with my own experience of why I resonate with religious ritual, because it touches something deep within that has nothing to do with reason or logic. I love the ritual of the Catholic Mass, for example, and I’m attracted by the whole ambience of Catholic churches. I’ve had lifelong fantasies of being a Catholic monastic (Brother David Steindl-Rast describes the vocation of a monk as “being entirely present in the given moment… being alive in the Now,” so perhaps I am a kind of hermit monk), but of course I could never actually join the Catholic Church because I don’t believe in the dogma, the creed, the infallibility of the pope, the social conservatism or the patriarchal hierarchy. But still, the ritual and the symbolism and what it evokes touches me deeply. I love listening to Gregorian chants and I resonate with Christian mystics like my dear friend John Butler (who likes to call himself Mr. Nothing) or the late Father Thomas Keating.

Thomas Keating, who was a Trappist monk, described God as “emptiness containing infinite possibilities” or “absolute Nothingness.” As I’ve written in the new book I’m working on:

God is pure potentiality, the germinal darkness out of which everything emerges, the zero on which all other numbers depend, the very core of our being, the timeless eternal unicity, the sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere, that which is subtlest and most intimate. God is a way of seeing, seeing the sacred everywhere, seeing the light in everything, beholding it all from love, from the perspective of wholeness—seeing and being the whole picture. God is unconditional love. Awakening is about opening to God, allowing God, abiding in God, dissolving into God. When I open to God, immediately there is no me and no God; there is only this vast openness. God is at once most intimate, closer than close, and at the same time, transcendent. God is not other than this presence here and now, and yet, God is also a relationship, a dialog of sorts, a way of listening to myself and the whole universe. God is impossible to define or pin down.

In some sense, for me anyway, the desire for a specific religion or for “the right church” or “the right Zen center,” is about wanting a form in which to let go into formlessness, a container of some sort, a launch pad, a place to land, an anchor—and also a community, a place to belong. But the truth is, I find all this more potently in nature, sitting by the pond, with nothing to grasp. And perhaps surprisingly, also in city streets and myriad other places not usually associated with spirituality.

At the same time as I was reading the novel Stone Yard Devotional, I was also reading a beautiful book called Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America by Chris Arnade, which I very highly recommend it. It’s a book of photographs and text by a man who spent several years crossing this country, hanging out in places where the industries and the jobs have left, places that are run down, places where there is poverty, homelessness, prostitution, addiction and yet also resilience, community and faith. Arnade has a PhD in physics and had a career on Wall Street. He always liked to walk, and at some point in his Wall Street career, he started taking walks into the neighborhoods in New York City that everyone said were unsafe and best avoided, photographing people and listening to their stories. Finally, he quit his job on Wall Street and began traveling to “back row” places all around the country, listening to people, photographing them, hearing their stories. In every town he visits across America, he always hangs out at the McDonalds, which he discovers is a kind of community center for the dispossessed, and although he is an atheist, he always goes to one of the local churches. He discovers the importance of faith in the lives of many of the people he listens to and photographs, and he comes to respect religion, seeing it as something potentially useful and life-sustaining that he has no impulse to disparage or undermine. He presents the people he photographs and talks with in such a way that we see their beauty, their resilience and their dignity, and his whole journey seemed to me to be a spiritual or religious journey in the deepest sense, although Arnade might not see it that way. But in the way he interacted with people and saw them, he very much seemed to me to embody the spirit of Jesus, who in my reading of the Gospels was someone who faced and transcended the worst kinds of human suffering and who was always a friend of the dispossessed.

Religion or spirituality, as I mean it, is about abiding in openness or groundlessness, which is another word for God. It’s about recognizing wholeness and the absence of separation. It’s about noticing the dream-like nature of experience and the unresolvable, non-substantial nature of everything that appears, and at the same time deeply appreciating the sacred in every appearance. It’s about questioning all our certainties and beliefs and discovering what remains when we let them all go—what is here now that cannot be doubted. It’s about devotion to the gift of every moment. It involves mysteries and truths beyond where reason and logic can go. It’s about finding the way through suffering to liberation, from the crucifixion to the resurrection, not once and for all, but again and again, always now. It’s about finding the love, the joy, the beauty, and the peace right here in this one bottomless moment. It’s about being and living from unconditional love.

And of course, we fall short. We lose faith. We feel lost and forsaken, separate and alone. We give in to temptation, addiction, despair, worry, and mean-spirited behaviors. So the religious journey is always a dance of doubt and faith, crucifixion and resurrection, the human and the transcendent, the limited and the unlimited, duality and non-duality, relative and absolute. But over time, we come to know directly, beyond any doubt, the wholeness of presence, and we can discern more and more immediately what feels wholesome and what feels like delusion, and as the light of awareness reveals delusion as delusion again and again, it begins to gradually lose its persuasiveness and its grip. And as we taste wholeness more and more fully, it draws us into itself more and more.

At some point, we may come to a deep realization that wholeness is ever-present and all-inclusive—and we come to understand that even if we sometimes feel separate, lost, confused, anxious, worried, depressed or totally bewildered, this is simply a passing appearance, and that wholeness can never actually be lost. It includes everything.

There is a common factor in every different experience, whether we seem to be joyously walking on water or sinking and drowning in doubt. All of it is this luminous radiant presence that is ever-changing without ever departing from the immediacy of right here, right now, and all the shapes it momentarily takes are a kind of passing dream in this dreaming presence that includes it all. By paying attention to life itself (or by doing something like The Work of Byron Katie or cognitive therapy), we can see that the thoughts that tell us otherwise are just thoughts. They may still arise, but we no longer believe them, or not for long.

Words are never quite right, but this, in my experience, is the pathless path through the gateless gate to the placeless place where we always already are, aka the religious journey of faith, sometimes known as walking on water.

A very beautiful 14 minute video of Sufi teacher Pir Elias Amidon that I very highly recommend:

Love to all…

Thanks Joan! As a child my parents used to take me and my siblings to the Catholic Church. As soon as I was old enough I started taking myself to my preferred 11.00 a.m. sung mass in Latin. It was an exquisite delight to hear and sing these nonsense Latin syllables with a group of others. I used to come back from the communion and close my eyes and go into what I later recognised as meditation. Often I would see/feel an image of a blue-white light that enveloped me and I thought of this as the presence of Jesus. When I was about 10 years old I joined a small cultic group within the church called "Legio Mareae", the Legion of Mary, where we would pray to Mary and repeat a small phrase with her name over and over. On the way to church I would pass by a small hall that was rented out to a Swaminaryan Hindu group and where I first heard the clash of cymbals and rhythmic repetitive chanting that was my first exposure to Indian bhajans. I remember the joy that was pouring out from that hall and my desire to be inside chanting with them. About age 12 or 13 I became aware of the intense hypocrisy and actual evil intent behind some of the representatives of this religion and started to distance myself from it. I took LSD at age 15 and after my second trip and dissolution in the Clear White Light of the Void, nothing was quite the same again! I quit Catholicism, but several years later, vegetarian, drug free and after shaktipat in a Hindu Ashram, I found myself once again singing nonsense syllables in a group with everyone intending to make the most beautiful vibration possible. Like children, we were simply making sound vibration for the sheer delight. I found myself leaving that group too, but the delight in sound-vibration-joy never left me. Alleluia!

‘Walking on water’ is how I would describe the leap of faith I’ve made in my own life recently. Wonderful post Joan ❤️